by Maya Drozdz

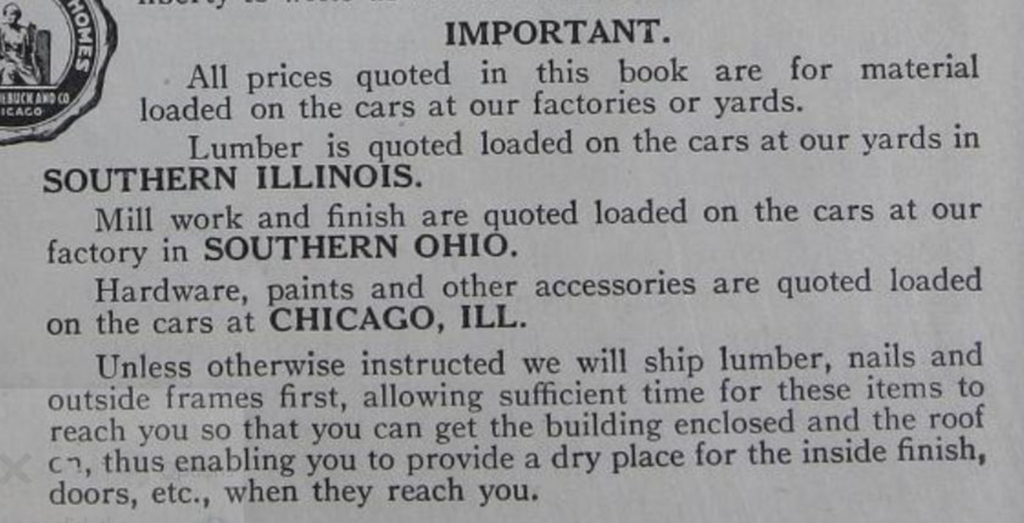

Between 1908 and 1940, Sears Roebuck plied the materials and kit home market with its home plans and several lines of ready-to-build home kits. The Modern Homes program was spearheaded by Frank W. Kushel, the Sears china department manager who had been tasked with dismantling the unprofitable building materials department. Instead, Kushel developed a bundling model that successfully sold over 75,000 packages of building materials to customers all over the US. These were chosen through a mail-order catalog and shipped to a train depot near the building site (depending on the destination, they were occasionally shipped by barge).

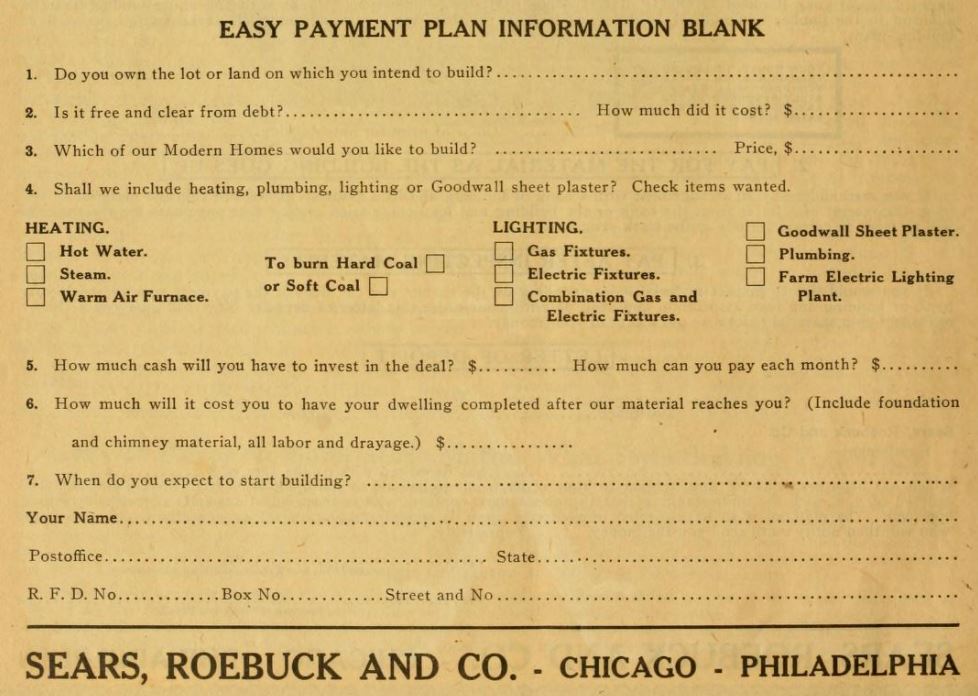

In 1911, Sears Roebuck added home financing to its suite of offerings, filling a growing need among the middle- and working classes, including many recent European immigrants who had been shut out of the home-buying process. The financing application form contained no questions about race, ethnicity, gender, or even finances; suddenly thousands of formerly ineligible buyers were absorbed into the new-home market. The company ended its home lending program in 1934 with the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration.

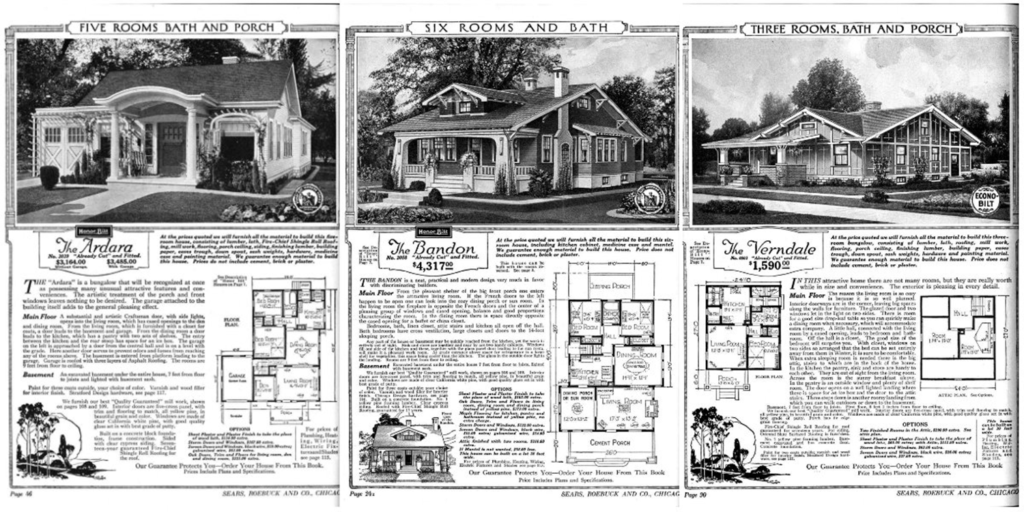

Three product lines were offered. The panelized Simplex was prefabricated and typically purchased for use as a garage or cabin. Honor Bilt, the premium home option, used high-quality materials and heavy framing. Standard Built (also known as Econo Bilt or Lighter-Built) homes tended to be small, with less insulation, well-suited for warmer climates. Some designs were offered in both Honor Bilt and Standard Built versions.

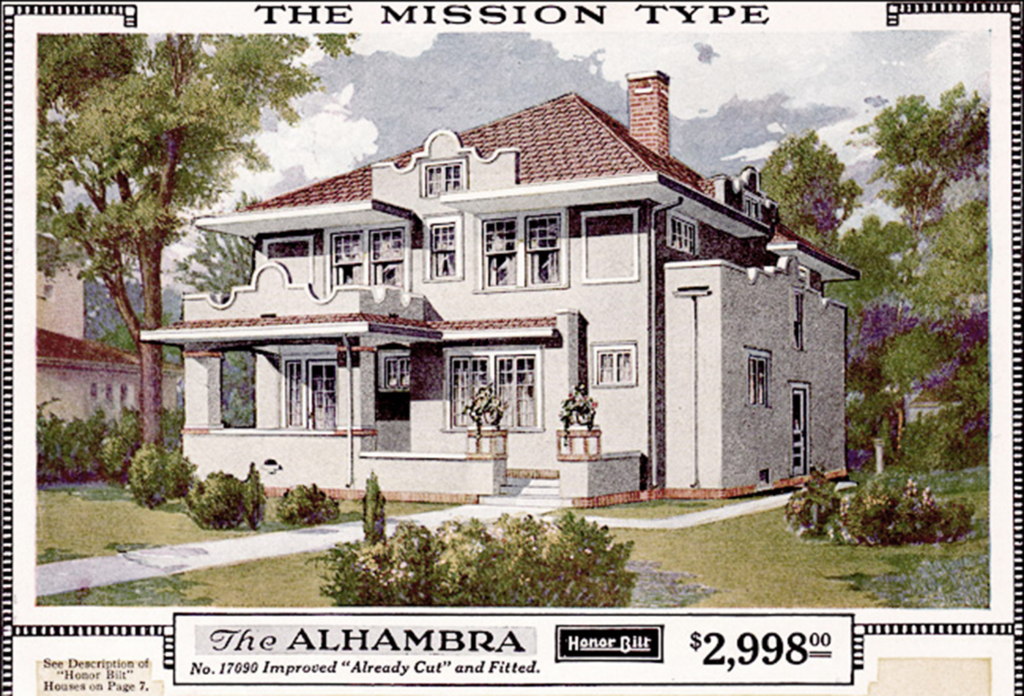

The catalogs, sometimes published twice a year, marketed varied traditional home plans, almost 450 different designs over the years, beginning with simplified Queen Anne styles in the 1910s, and continuing with English Cottage, Dutch Colonial and other eclectic and revival styles through the 1930s. The models were initially numbered, but Sears soon started giving them evocative names, like the Colonial Revival Betsy Ross, Spanish-style Alhambra and Dutch Colonial Revival Rembrandt.

The range of traditional facades contained many interior innovations of the time. Central heating, indoor plumbing and electricity were incorporated into many of the home plans, or could be added. Other features included built-ins like china cabinets, ironing boards, medicine cabinets, and telephone niches.

Because freight transportation was a key factor in the final price, many of these homes were clustered near Sears factories and railroad lines in the Midwest, with the highest concentrations found in Ohio, Michigan and Illinois. In 1912, Sears & Roebuck purchased a millwork plant in Norwood, and its Cincinnati sales office opened in 1921. According to an advertisement in the Cincinnati Enquirer, 3,000 Sears homes had been built locally by 1930!

Close to Madisonville’s border with Oakley, the Eastwood Historic District includes 66 modestly-scaled houses built prior to 1950, 19 historic pre-1954 garages and a cabin. 10 are Sears kit homes, though one is non-contributing. Although each house is unique, there are many commonalities in the styles and materials chosen (including the non-Sears homes this tour skips). The enclave has the feel of a small English village, a quality possibly inspired by the nearby planned community of Mariemont (Eastwood was platted in 1922, and ground broke on Mariemont’s development the following year).

Our tour starts at 5018 East Eastwood Cr. and continues counterclockwise through the cul de sac. Built in 1930, this is the Osborn model, designed by architect Andrew F. Hughes and described in the Sears catalog as a “stucco and shingle sided bungalow in Spanish mission architecture” with “massive stucco porches and bulkheads.” Sears sold this model from 1916 until 1929. All of the original features are still present; the home is currently undergoing renovation.

The Verona model at 5032 East Eastwood Cr. was one of several Dutch Colonial Revival house plans offered in the Sears 1923 Honor Bilt Modern Homes catalog. According to marketing materials, this was a “high class” home, with features including a reception hall and first-floor powder room. “Built many times in the exclusive suburbs of New York, Chicago, Washington, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and other large cities. Aside from its rare beauty, it represents one of the best values in this catalog.”

5038 East Eastwood Cr. is the 1932 Puritan model, a Dutch Colonial Revival home designed specifically for a narrow lot. In the 1970s, an addition was built on the south side, above the optional sun room. The wood siding on the home is original, with carefully matched wood siding on the addition.

Built in 1933, 5046 East Eastwood Cr. is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Maplewood model with an Osborn roof line. Maplewood was offered 1930-1932; in 1933, the Maplewood name was dropped and replaced by Ridgeland, though the design did not change. Since this home was constructed in 1933, it may actually be a Ridgeland, which was offered until 1940. (Click here for more information about Maplewood/Ridgeland.) In any case, the design features a massive brick and stone chimney next to a flared front-facing gable, and a flared ridge on the steeply pitched roof.

5050 East Eastwood Cr. is a fine example of the English Cottage-style Mitchell model, built in 1933. The current owners removed unsympathetic vinyl siding to expose the original shingles. According to the marketing materials, “At first glance, the roof might appear difficult to erect, but with our perfected ready-cut method of construction, every rafter is cut to exact length, with the corner miter, so that it will fit as intended.” At 974 square feet, this is the smallest home of the Sears group in the Eastwood Historic District.

The Sunbeam model at 5054 East Eastwood Cr. was a perennial best-seller from the premium Honor Bilt line, marketed as a “modern bungalow.” This home, built in 1933, features steps on the side leading to a substantial front porch, with an enclosed sleeping porch above. The clapboard siding and wood shingles are original.

5066 East Eastwood Cr. is the 1930 Crescent model, a Colonial Revival with a centered portico covered with a prominent pediment. The pediment was not in the Sears house plan but may be original to the home’s construction. Crescent was a mainstay in the catalog, appearing 1920-1933. Here, the distinctive wooden porch posts of the original design have been replaced. (Click here to learn about the challenges of identifying a Crescent in a sea of lookalikes.)

5061 West Eastwood Cr. is the Martha Washington, another best-selling Honor Bilt model. Built in 1933, this is a Dutch Colonial Revival with fluted porch columns, and a front door flanked by sidelights with an elliptical fanlight above. Marketing materials described the home as “commodious,” with “a design that will delight lovers of the real Colonial type of architecture.”

Built in 1925, 5031 West Eastwood Cr. is a non-contributing property due to heavy modifications to the original design. What now looks like a garden variety American foursquare was originally built as the fanciful Mission-style Alhambra, a best-selling model dubbed “an architect’s masterpiece” in the home’s marketing materials, and offered from 1918 until 1929. (Click here for exterior and interior photos of an intact Alhambra in South Dakota, and here for other Cincinnati-area Alhambra models.)

We end our tour with the Wayne model at 5023 West Eastwood Cr., built in 1932. The symmetrical front facade has a large front porch, large windows and a front-facing gable roof. The Wayne was offered 1925-1931; the model is almost identical to the earlier Delmar, which appeared in the 1924 catalog. (Click here for some tips to identify a Wayne.)

The great variety of models, plus modifications over the years, can make it difficult to authenticate a Sears home, or that of its many kit house competitors. (Click here to learn exactly how challenging authentication can be.) There was never a “typical” Sears house, and the company also encouraged buyers to customize the plans. Buyers could even design their own homes and submit the blueprints to Sears, which would then deliver a one-off kit of pre-cut and fitted materials, putting the home owner in full creative control.

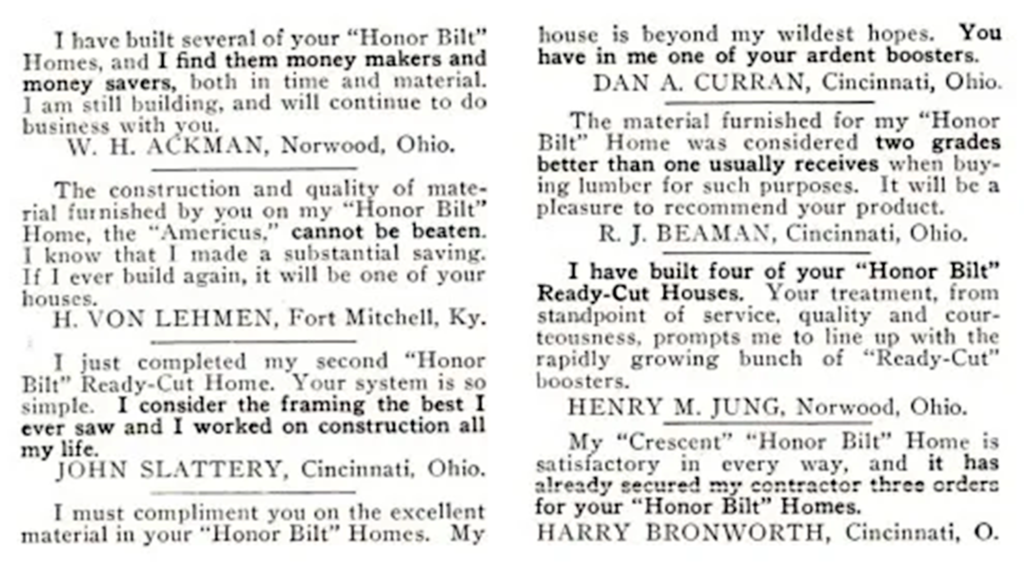

The deliberately traditional designs were built individually by buyers or in clusters by developers, and blend in with other homes of the era. Regardless of style, they were a big hit in Cincinnati:

Unfortunately, a few years after the Modern Homes program ended, Sears destroyed all sales records in a corporate housecleaning, and subsequently collected information is incomplete and decentralized. However, many resources exist to aid in research and authentication; below is a sample.

References: