by Maya Drozdz

The idea of mass-produced buildings is not new. In 1801, British manufacturers began fabricating cast iron structural systems for industrial buildings, a concept that was extended to storefronts and even entire facades ordered through catalogs, which became popular across the US by the late 19th century. Many fine examples can still be found in older Cincinnati neighborhoods such as Over-the-Rhine.

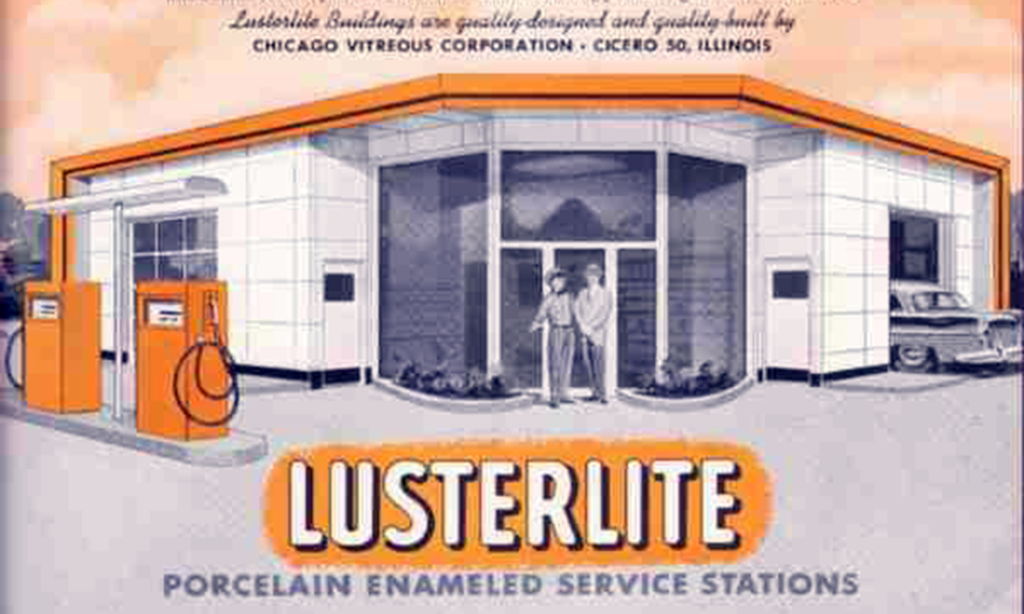

The process of enameling metal sheets was developed in the mid-1800s. Porcelain enamel was strong, fade-resistant and easy to clean, and was quickly adopted by manufacturers of signs, appliances, and bathroom and kitchen fixtures. Metal enameling was being done on an industrial scale in the US by the end of the 19th century.

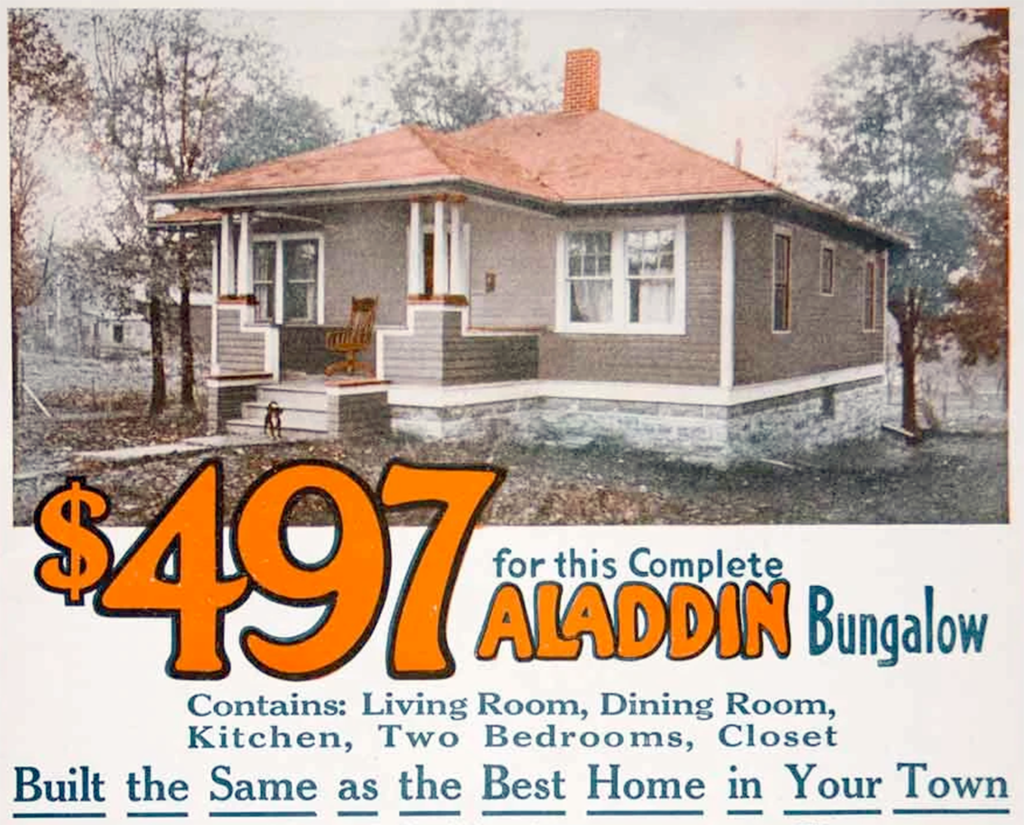

In 1906, Aladdin Homes began producing home kits consisting of pre-cut pieces that could be assembled by the home owners themselves (although professionals were frequently hired for the task). Like the cast iron storefront components, these were marketed through mail-order catalogs. Soon, other companies entered this emerging market, most notably Sears, Roebuck & Co., which sold over 75,000 kit homes between 1908 and 1940. (Aladdin continued production long after its competitors stopped, finally closing its doors in 1981.)

The output of the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Company, founded in 1919, helped to popularize use of porcelain enamel in utilitarian structures like gas stations and fast food stands. (The American Sign Museum has a fine example of a 1940s porcelain enamel storefront on display. Rohs Hardware was once located on Vine St. in Over-the-Rhine, and the facade now lives in the museum’s Main Street exhibition.)

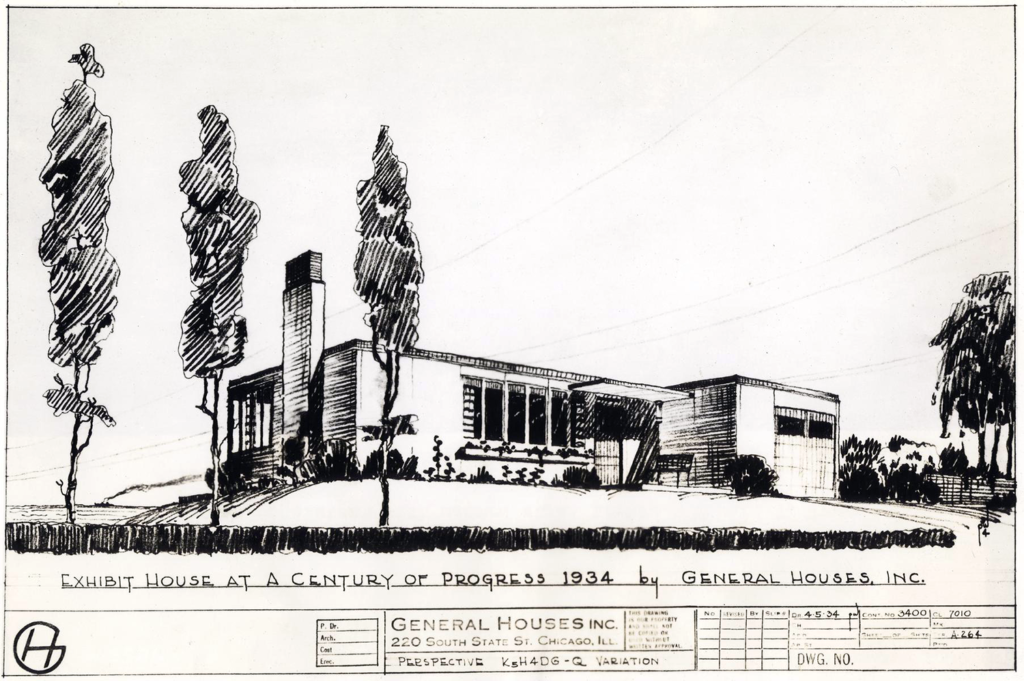

By 1932, General Houses, Inc. was producing small, prefabricated units using steel construction as well as utilizing metal as an exterior and interior finish material. The following year, over a dozen companies developing prefabricated steel housing exhibited models at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago. By 1935, the majority of prefabricated housing companies were utilizing steel in their designs.

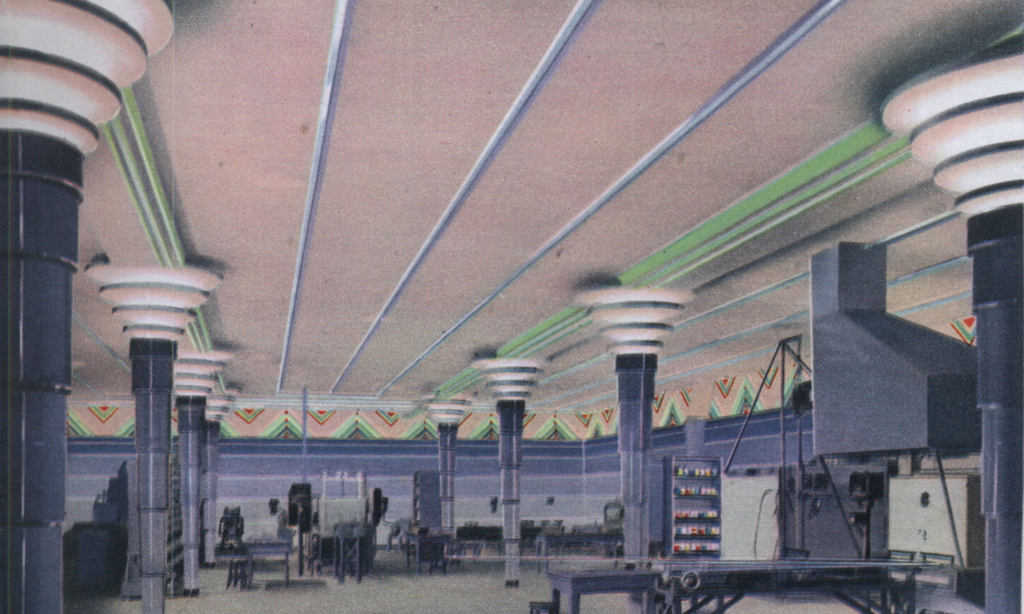

During World War II, housing production in the US practically stopped, as necessary materials, factories and labor were needed to support the war effort. The Chicago Vitreous Enamel Company hired Swedish-born Carl Gunnar Strandlund to retool its plant for tank armor production. Meanwhile, the military continued innovating prefabrication methods and developing structures that could be assembled by unskilled laborers.

Toward the end of WWII, Strandlund obtained a patent for construction using interlocking porcelain enamel panels. His invention applied the use of this sleek material to prefab housing and offered, in his words, “a new way of life. [This home] can be mass-produced, handled by local dealers, transported to a new locality if desired, even traded in on a larger model.” In 1947, he established the Lustron Corporation and accepted the first of several multimillion-dollar loans from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to start producing the futuristic homes for returning GIs and their growing families.

Strandlund had competition in the form of almost 300 other companies, many of which also utilized prefabrication, vying for federal funding to address the housing shortage, but the government chose to only work with three, with the Lustron Corporation receiving by far the most support.

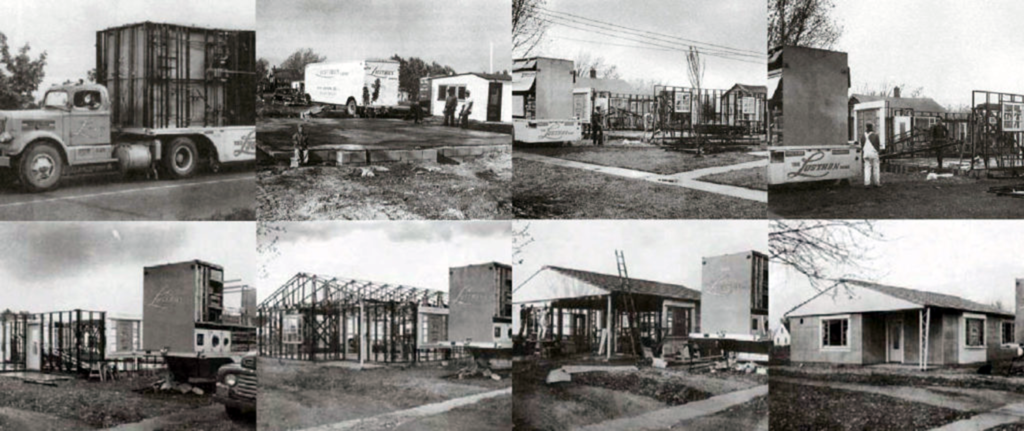

Lustron was based in the former Curtiss-Wright manufacturing plant in Columbus, OH, and soon these homes were being sold through a network of about 230 builder-dealers in 35 states, who sold and erected each house package on a concrete foundation, in some cases securing a suitable parcel of land as well.

Unlike Sears, Aladdin and the other kit home manufacturers, which were offered primarily in traditional and widely accepted styles, designed to blend into communities, Lustron was unabashedly contemporary inside and out. Unlike the many catalog offerings, these homes only came in four basic models — Westchester, Westchester Deluxe, Newport, and Meadowbrook — with 2- and 3-bedroom variations. The signature porcelain enamel exterior finish came in a choice of only four colors (Surf Blue, Maize Yellow, Desert Tan, and Dove Gray). Each home came with a plaque with an embossed model and serial number, and an owner’s manual, as if it were a car or appliance.

A Lustron home announces itself from a distance, proudly exhibiting its panelized construction and novel use of materials. While kit homes can nowadays be a challenge to authenticate, given the many options and subsequent alterations, these homes, even when modified, retain their post-WWII futuristic essence. To borrow a phrase from Le Corbusier, a Lustron home is truly “a machine for living in.”

The interior photos below are of 2700 Flemming Rd. in Middletown, a remarkably intact Lustron home that’s currently on the market.

Inside, the interior focuses on streamlined efficiency, with space-maximizing pocket doors, closets and built-ins. About 20% of the interior space is storage! The walls and ceiling are made of pale gray metal panels, intended to never be painted. (“Permanent finishes cut down maintenance costs” claimed the marketing materials.) Optional picture-hanging kits and steel venetian blinds could be purchased to customize the space. The original kitchens featured an innovative under-the-sink Thor Automagic, which easily converted from a dishwasher to a washing machine.

The homes were marketed as sanitary and “almost maintenance-proof,” the materials protecting against damage from termites, vermin, fire, saltwater, and lightning. Even limitations were described as features. “Lustron Homes have walls of permanent washable porcelain enamel and will never need redecorating.” “The convenience of one-floor living—no stairs to climb.” “The Lustron Home is designed with maximum storage and service facilities on the first floor. A basement—the old necessary evil—is not needed.”

Even with federal subsidies, the company was only able to fill 2,680 of the more than 20,000 orders it received before declaring bankruptcy in 1950. Why? Accounts vary, but a few problems evident from the start were never overcome. Tooling the factory for production was more difficult and expensive than originally estimated. Each home was made up of too many unique parts for production to truly be efficient. The company relied on a network of dealers whose startup costs were exceedingly high. Building codes were a problem in some communities. Production was unable to break even or keep up with demand, and construction took much more time and labor than projected.

275 Lustron homes were constructed in Ohio before the company folded. Several can still be found scattered in Silverton, Mount Washington, Sycamore Township, Wyoming, and Middletown. Some see these homes as a relic of the past future that never materialized, while others appreciate their smart use of space, perfect for the era of the Tiny House. Some, like the Surf Blue home in Wyoming, feature a well-preserved exterior (note the original zigzag downspout that can double as a trellis) with an interior that’s been completely renovated to suit contemporary needs and tastes. But others, like the well-preserved Maize Yellow example in Middletown that’s currently on the market, continue to inspire as a time capsule of late 1940s home innovation. (Click here to see a sensitive update that respects the unique design and interior features of a Lustron.)

References: